The information on how best to eat has changed radically in the last few years. After being demonised for decades, fat is now known to be vital to our well being and surprisingly not only doesn’t make us fat, but helps with weight loss. Sugar and carbohydrates from grains are now considered to be one of main causes of the huge increase in obesity and resulting health problems globally.

In our book, The In-Sync Diet, nutritionist Fleur Borrelli and I talk about the many benefits of eating protein. We particularly recommend fish, poultry and eggs. However, there are others who say that too much protein is not good and that some meats are even bad for us. There is much debate going on about the merits of protein. It’s all quite confusing.

Here, Fleur looks at the facts from the most up to date information available.

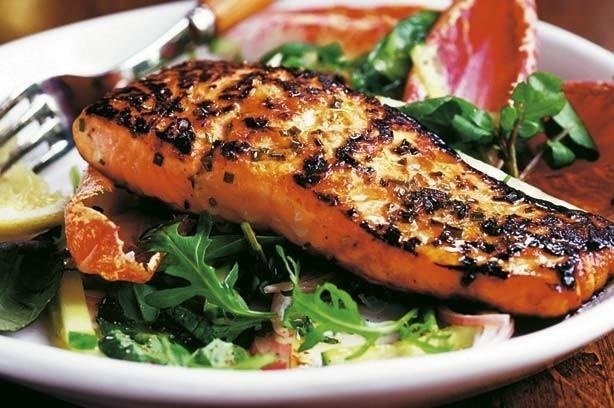

Image courtesy of Good to Know

Proponents of Atkins or Paleo style diets often find themselves in the cross hairs because they advocate eating moderate to high amounts of animal protein. Why is this the case?

Interestingly, long before Atkins launched his high protein/low carb diet in 1972, an overweight British undertaker named Banting was put on a similar diet in the 1800’s by his doctor to drop a few kilos. He then wrote a 20-page letter which was published in 1863 describing how he had tried many diets, but this approach to eating was the first that had any success. ‘Starch and sugar are the culprits’ he said ‘cut them down and eat fat and protein (1). This became the accepted view until the 1950’s when it was realised that heart disease and obesity were on the increase. (2). Based on the flawed interpretation of a scientific study from a biologist Ancel Keys, recommendations on our intake of animal protein were revised.

The category ‘animal protein’ encompasses red meat (beef, lamb and pork), white meat (chicken and other poultry), fish and eggs. There is little or no evidence that white meats, fish or eggs contribute to increased rates of disease. Fish is an important source of protein and particularly essential fats that we need from our diet because we cannot produce them ourselves. Oily fish such as mackerel, anchovies and sardines are especially beneficial for the brain, the nervous system and the cardiovascular system.

Red meat consumption has been linked to inflammation and a higher incidence of colorectal cancer although this research is now being questioned (3). Despite the lack of controlled trials demonstrating that red meat is inflammatory, there has been recent concern over a compound in red meat called Neu5Gc that has been linked to cancer (4). Neu5Gc is a sugar molecule from mammals that can stick to the outside of all our cells. In other words when we consume red meat and milk products, we incorporate some of this compound into our own tissues which can cause an immune reaction and inflammation leading to chronic diseases such as cancer and autoimmune diseases (5).

Extra care must be taken when cooking all meat. Carcinogenic compounds such as heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may be produced when meat is charred (6). If you do want to grill or fry your meat you can significantly reduce the formation of these compounds by using a marinade. Processed meats that contain nitrates, used as preservatives, should also kept to a minimum.

But despite all the horror stories there is an emerging body of evidence showing that greater amounts of high quality proteins, such as eggs, chicken and fish, have a range of health benefits that extend beyond the maintenance of bones, muscle mass and essential metabolism. These may include body weight and fat mass loss, maintenance of lean mass and reduced risk of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (7).

- http://www.lowcarb.ca/corpulence/corpulence_full.html

- http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7654

- ncbi.nlm.gov/pubmed/2594180

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19017806

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25003133?dopt=AbstractPlus

- http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/diet/cooked-meats-fact-sheet

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25926512